“With the Islamic Arts Biennale, we are working to enable a deeper and more nuanced exploration of the Islamic arts,” says Farida Alhusseini, director of the Islamic Arts Biennale.

The Islamic Arts Biennale, set to “bridge the past, present, and future,” has opened at the 1983 Aga Khan Award-winning Western Hajj Terminal in Saudi Arabia’s Jeddah.

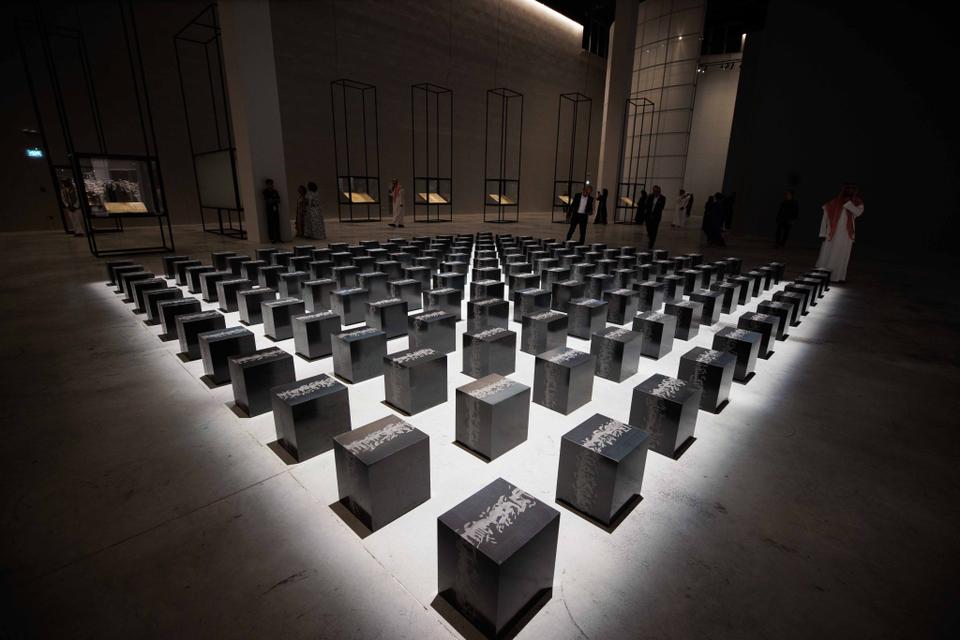

The biennale’s theme, Awwal Bait, meaning “First House,” referring to the Holy Kaaba in Mecca, showcases the works of over 60 well-known and emerging artists from around the world, in addition to over 60 new commissions, 280 artefacts, and more than 15 never-before-exhibited pieces of art, from January 23 through April 23.

In using this venue, the biennale’s geographic significance is further highlighted. For centuries, Jeddah has served as a crossroads for cultural exchange and a port of entry for pilgrims travelling to Mecca and Medina. The occasion summons a call to pause and consider the rituals that act as personal compass points, while also having the power to foster a sense of community and belonging among people.

The biennial’s extended scope includes contemporary artworks as well as design and architectural pieces, crafts and works from other fields as it explores the influence of Islam on cultural life.

With over 12,000 square metres of exhibition space to explore, the visitor is invited to embark on an evocative trip through five galleries and a vast canopy. The biennale has two primary exhibition spaces for art and artefacts: The first is a series of interior galleries, while the second is made up of the Mecca and Medina pavilions and an outdoor space beneath the roof of the Hajj Terminal.

Dr Saad Alrashid, a renowned archaeologist and scholar; Dr Julian Raby, former director of the National Museum of Asian Art of the Smithsonian Institution; and Dr Omniya Abdel Barr round out the impressive curatorial team alongside architect Sumayya Vally. They come together with their significant use of mediums, techniques and practices, as well as the shared themes of spirituality, collectiveness and belonging that they explore in their own works.

One of the most renowned curators among them, Sumayya Vally, co-founder of Johannesburg-based architecture and research practice Counterspace, draws inspiration from her own personal experience of the Hajj Terminal as a pilgrim and expresses how impressed she was upon witnessing the world gather under this “infinite canopy” as people from different cultures and speaking different languages shared food, led each other in prayer and waited for hours in the same place — a scene she defines as demonstrating an “immense sense of community.”

“It’s this sense of belonging that the programme seeks to explore,” she added. “I think that spirituality is found in ritual practice; it’s not necessarily found in any ornate or overt construction alone.”

The event is not an “ordinary” biennale, but rather “a very structured, almost theatrical exhibition,” says curator Julian Raby, director emeritus of the National Museum of Asian Art at the Smithsonian Institution, adding that the Islamic Arts Biennale “is very much about the emotional side of some of these rituals” —“I could imagine an anthropological museum could discuss prayer, but it would be a very dry to scripted thing about the feelings.”

Embodied emotions

The biennale experience is supposed to reflect the journey of the soul because it starts in the dark and moves toward the light.

As guests enter, they come upon American-Lebanese artist Joseph Namy’s latest project, Cosmic Breath, a collection of recorded calls to prayer from various nations and eras are played in harmony, presenting an everlasting, undulating call.

The installation Wave Catcher, created by Saudi artist and researcher Basmah Felemban, materialises the adhan (Islamic call to prayer) into a succession of waveforms, representing the breath Muslims take in between each verse and phrase.The term “buhur,” which means “seas” in Arabic, is used to define the poetic metres that control the adhan’s phrases, pitches, and inflections, according to Vally.

Adhan is the Islamic call to public prayer (salah) in a mosque, recited by a muezzin at prescribed times of the day.

The biennale proceeds through themes of water and Wudu, a purification ritual. With pieces of fired clay of various colours acquired from all over his country, Moroccan artist M’barek Bouhchichi explores the beauty of the breadth of Islam in his latest commission, Kolona min Torab, “Everyone is from Earth.”

The funeral procession of Imam Abdullah Haron, a Muslim community leader who was assassinated by apartheid police in 1969, is the focus of Amongst Men, an existing work by South African author Haroon Gunn-Salie which he further expands. The piece includes 1,000 cast kufiya hats, along with readings from his daughter and widow at funerals. “These are the things that we leave behind us after we die,” says Vally, adding that the performance emphasises acts of kindness and justice as forms of worship.

Outside, the biennale explores the many ways people assemble and build communities, particularly with regard to the Hejaz as a hub for cultural interchange. One such is Syn Architects’ Anywhere Can Be A Place of Worship, an architecsite reflects the old space from time of Prophet Muhammad.

The terminal all showcase historical artefacts that were once kept in the Prophet’s Mosque in Medina and the Masjid al Haram in Mecca, as well as modern artistic creations that were influenced by these holy sites.

Source: TRTWorld and agencies

Islamic Arts Biennale: Mirroring the journey of the soul

Source: News Achor Trending

0 Comments